Video Notes

Key Insights22 highlighted

Machine learning and neural networks are highly relevant for solving such complex recognition problems that humans find trivial.

A neuron in a neural network is conceptualized as a unit that holds a numerical value, specifically an 'activation' between 0 and 1.

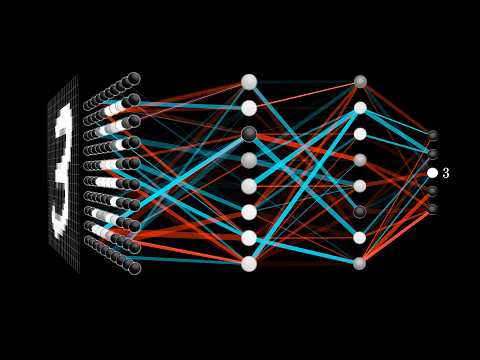

The network's input layer comprises 784 neurons, each corresponding to one of the 28x28 pixels of an input image, with its activation representing the pixel's grayscale value (0 for black, 1 for white).

Note:

The output layer contains 10 neurons, each representing a digit from 0 to 9, where its activation indicates the network's confidence that the input image corresponds to that specific digit.

Intermediate 'hidden layers' exist between the input and output; in this example, there are two hidden layers, each with 16 neurons, a choice made for illustrative purposes.

Note:

The network operates by having activations in one layer determine the activations of the subsequent layer, forming the core information processing mechanism.

When an image is fed into a trained network, the input layer's activation pattern propagates through the hidden layers, culminating in an output pattern where the brightest neuron signifies the network's recognized digit.

A key hope for the hidden layers is that individual neurons within them will correspond to and activate upon detecting these specific subcomponents, like an 'upper loop' or a 'long vertical line'.

The recognition of complex subcomponents, such as a loop, can further be broken down into the detection of even smaller, more fundamental elements like various 'little edges'.

The mechanism by which activations in one layer determine those in the next involves assigning a 'weight' to each connection between neurons.

The activation of a neuron in a subsequent layer is computed by taking the weighted sum of the activations from all connected neurons in the preceding layer.

Weights can be visualized as a grid, where positive weights (green) highlight relevant pixel regions and negative weights (red) can be used to detect patterns like edges by contrasting bright central pixels with darker surroundings.

To ensure neuron activations remain between 0 and 1, the calculated weighted sum is passed through a 'sigmoid function' (also known as a logistic curve), which squishes the entire real number line into this range.

The sigmoid function maps very negative inputs close to 0, very positive inputs close to 1, and shows a steady increase around an input of 0.

An additional numerical value, called the 'bias,' is added to the weighted sum before it enters the sigmoid function, allowing the neuron to activate only when the sum exceeds a specific threshold (e.g., greater than 10 instead of 0).

The entire network, including connections between all layers, has approximately 13,000 total weights and biases, representing a vast number of adjustable 'knobs and dials'.

In neural networks, 'learning' refers to the process where the computer automatically finds optimal settings for the thousands of weights and biases to effectively solve the given problem.

The connections and activation transitions between layers can be compactly represented using linear algebra: activations are vectors, weights are matrices, and biases are vectors.

Note:

The calculation of weighted sums and bias additions is efficiently expressed as a matrix-vector product plus a bias vector, with the sigmoid function applied element-wise to the resulting vector.

Historically, early neural networks utilized the sigmoid function to map weighted sums to the 0-1 range, drawing inspiration from the biological analogy of neurons being either inactive or active.

However, modern neural networks rarely use the sigmoid function due to difficulties in training; instead, they predominantly employ activation functions like ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit).

ReLU, which stands for Rectified Linear Unit, is a simpler function that outputs the maximum of zero and its input (max(0, a)), serving as a more effective and computationally efficient alternative for deep neural networks.